- Home

- Jenni Fagan

The Panopticon

The Panopticon Read online

Contents

About the Book

About the Author

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Book

Pa‘nop’ti‘con (noun). A circular prison with cells so constructed that the prisoners can be observed at all times. [Greek panoptos ‘seen by all’]

Anais Hendricks, fifteen, is in the back of a police car, headed for the Panopticon, a home for chronic young offenders. She can’t remember the events that led her here, but across town a policewoman lies in a coma and there is blood on Anais’s school uniform.

Smart, funny and fierce, Anais is a counter-culture outlaw, a bohemian philosopher in sailor shorts and a pillbox hat. She is also a child who has been let down, or worse, by just about every adult she has ever met.

The residents of the Panopticon form intense bonds, heightened by their place on the periphery, and Anais finds herself part of an ad hoc family there. Much more suspicious are the social workers, especially Helen, who is about to leave her job for an elephant sanctuary in India but is determined to force Anais to confront the circumstances of her birth before she goes.

Looking up at the watchtower that looms over the residents, Anais knows her fate: she is part of an experiment, she always was, it’s a given, a liberty – a fact. And the experiment is closing in.

In language dazzling, energetic and pure, The Panopticon introduces us to a heartbreaking young heroine and an incredibly assured and outstanding new voice in fiction.

About the Author

Jenni Fagan was born in Livingston, Scotland, and lives in Edinburgh. She graduated from Greenwich University with the highest possible mark for a student of Creative Writing, and won a scholarship to the Royal Holloway MFA. A published poet, she has won awards from Arts Council England, Dewar Arts, and Scottish Screen among others. She has twice been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and was shortlisted for the Dundee International Book Prize. Jenni works as a writer in residence, in hospitals and prisons.

Jenni Fagan

THE PANOPTICON

For Joe & Boo

Sometimes I feel like a motherless child.

Traditional US folk song from the 1870s, a time when it was common to take children away from slaves in order to sell them.

When liberty comes with hands dabbled in blood it is hard to shake hands with her.

Oscar Wilde

i’m an experiment. I always have been. It’s a given, a liberty, a fact. They watch me. Not just in school or social-work reviews, court or police cells – they watch everywhere. They watch me hang by my knees from the longest bough of the oak tree; I can do that for hours, just letting the wishes drift by. They watch me as I outstare the moon. I am not intimidated by its terrible baldness. They’re there when I fight, and fuck, and wank. When I carve my name on trees, and avoid stepping on the cracks. They’re there when I stare too long or too clearly, without flinching. They watch me sing, and joyride, and start riots with only the smallest of sparks; they even watch me in the bath. I keep my eyes open underwater, just my nose and mouth poking out so I can blow smoke-rings – my record is seventeen in a row. They watch me not cry. They watch me lie like an angel, hiding my dirty feet. They watch me, I know it, and I can’t find anywhere any more – where they can’t see.

1

IT’S AN UNMARKED car. Tinted windows, vanilla air-freshener. The cuffs are sore on my wrists but not tight enough tae mark them – they’re too smart for that. The policeman stares at me in the rear-view mirror. This village is just speed-bumps, and a river, and cottages with window blinds sagging like droopy eyelids. The fields are strange. Too long. Too wide. The sky is huge.

I should be playing the birthday game, but I cannae, not while there’s witnesses around. The birthday game has to be played in secret – or the experiment will find out. What I need to do right now is memorise the number stickered inside the back window. It’s 75999.43. I close my eyes and say it in my head over and over. Open my eyes and get it right first time.

The car drives over a wee ancient stone bridge and I want to jump off it, into the river – the water is all brown whorls, but I’d still feel cleaner after. I slept in the forest for ten days once, it was nice; nae people, mostly. The odd paedo on the warpath like, so I had tae watch, but when it was safe, I bathed in the rapids. I washed my knickers and T-shirt in the current every morning – then dried them on rocks while I sunbathed.

I could live like that. Nae stress. Nae windows or doors. It must have been an Indian summer that year because it was still warm, even in September. I was twelve, and fucked, but not as fucked as now.

The policewoman lays her hand on my arm. She’s dealt with me before. She cannae see my nails are gouged into my fist. I didnae even notice until I uncurled my fingers and saw red half-moons on my palm.

I hate. Her face. The thick hair on his neck. I hate the way the policeman turns the wheel. What is worse, though, is this nowhere place. There’s nae escape. The cuffs chink as I smooth down my school skirt – it’s heavily spattered with bloodstains.

We drive by a huge stone wall, up to a gateway framed by two tall pillars. On the first there’s a gargoyle – someone’s stubbed a fag out in his ear. I glance up at the other pillar, and a winged cat crouches down.

My heart starts going, and it isnae what’s waiting at the end of the drive down there, or three nights with no sleep in the cells. It’s not the policeman smirking at me in his mirror. It’s a winged cat – with one red eye and a terrible smile.

Turn around and gaze back. That’s what the monk sent me, drawn on a bit of cardboard he’d ripped off a cereal box. One winged cat, in pencil – no note. He sent it from the nuthouse. Helen’s gonnae make me go and meet him, as soon as she gets back.

Look at it. A real stone winged cat! It’s stunning. His wings would be a couple of metres wide if he unfolded them, and there’s yellow lichen furring his shoulders. I’ll draw him, later, alongside my two-headed flying kitten, and a troop of snails on acid – wearing top hats, with spirally eyes and jaggy-fucking-teeth.

A sign for The Panopticon is nestled in trees with conkers hanging off them. A leafy arc dapples light onto the road, it flickers across my face, and in the car window my eyes flash amber, then dull.

The Panopticon looms in a big crescent at the end of a long driveway. It’s four floors high, two turrets on either side and a peak in the middle – that’ll be where the watchtower is.

‘They’ll not be scared of you in there,’ the policewoman says.

She undoes the chain from her belt to my cuffs. I scratch under my ponytail, then my leg. I’ve one of those wandering itches that won’t settle.

<

br /> There is birdsong. The smell of wet grass filters in the window – bark swollen by rain, mulch, autumn, a faint wisp of wood fire. The car pulls away from the leafy canopy into a sudden glare of sunlight and the policeman snaps his sun visor down, but he doesnae need tae, clouds are already racing down from behind the hills. A light drizzle glitters in the sun. There’ll be a rainbow after this.

Files marked A. Hendricks: Section 14 (372.1) are stacked on the front seat. My knees are itchy now. Funny things, knees, knobbly hunks of bone. The car stops outside a sign for the main entrance beside six shan cars and a minibus with Midlothian Social Work Department emblazoned on the side. I fucking hate travelling in those things.

Windows are open on the third floor but only about six inches – they’ll have safety locks on, so they dinnae get jumpers. Three girls hang out, although only their heads and arms fit through. They’re all smoking, and giggling to each other.

Up on the top floor, the windows are barred and boarded up. I bet there’s petitions to close this place down already; there’ll be people from the village writing letters tae their MPs. Mr Masters is right. He told us all about it in history – communities dinnae like no-ones.

Mr Masters said, in the old days, if a woman didnae have a husband or a family but she still did okay, people didnae like that. If there wasnae a male authority figure tae say she was godly – then they thought she was weak for the devil. Bound tae be bad. Or even if her crops were doing well, better than her neighbours, or she wasnae scared tae answer back? Fucking witch. Prick it, poke it, peel its fingernails off and burn it in the square for the whole town to see.

My shoes are tiny next to the policewoman’s, and my heartbeat’s too fast. I’m beginning to shrink, shrink, shrink, again! I fucking hate this. Everything recedes at the speed of light – the policeman, the car, even the white sun – until all that’s left is a tiny pinprick for me to stare back at the policeman. He’s saying something. His lips – move.

Gouge my nails back into my palms.

‘Aye, they’ll have you up on that locked fourth floor by teatime, Anais.’

Fuck off, wankstain. Stop looking at me. I need to just breathe, until this shrinking begins to give. It will give. It has to. The lassies are craning out their windows, trying to get the first look. They’ll already know – about the riots, the dealing, the fires, the fights. They’ll know there’s a pig in a coma.

At the middle window the dark-haired lassie is laughing. She’s got a curly moustache drawn on her upper lip. Next to her is a small blonde with a pixie haircut. She’s letting a long glob of saliva drool down, but it’s still attached to her mouth. The lassie at the end is wearing a baseball cap.

A shoelace hangs off the bar on the blonde girl’s window, but there’s nae fag on it – just an empty knot. Curly moustache is smoking it. Each unit does that. We tie shoelaces to the windows, so you can swing your fag, or joint, or whatever along after lights out.

‘Aye, you’re no gonnae be the smart cunt in there!’ the policeman says.

Focus on his face. It’ll help keep the shrinking back. He’s got green eyes, a squint nose, and the hair on his neck and forearms is thick as a fucking pelt. You’re giving me the boak, fuck-pus. He’s loving this. They’ve wanted me banged up away from town and their stations, for how long? They think if they put me far enough away then I cannae get in trouble. Aye. Okay. There’s still buses, fanny-heads, I umnay behind locked doors yet.

The policeman is watching me in his rear-view mirror. He gave me a stoater of a slap yesterday. Old radgio el fuckmong, I call him, old cunt-pus himself.

‘Smile, Anais, it’s a palatial country house, this!’

He gestures at the unit. It looks like a prison. It was one, once. And a nuthouse. He smirks again. I wish he was in a fucking coma.

The polis dinnae get it – we compare notes just as much as they do. We know if there’s a psycho in a unit, or a right bastard pig who’ll always batter you at the station. We know if somebody’s been stabbed, or hanged themselves, or who’s on the game, or which paedos in town will lock you in their flat and have you gang-banged until you turn fucking tricks. We send e-mails, start legends – create myths. It’s the same in the nick or the nuthouse: notoriety is respect. Like, if you were in a unit with a total psycho and they said you were sound? Then you’ll be a wee bit safer in the next place. If it’s a total nut that’s vouched for you, the less hassle you’ll get. I dinnae need tae worry about any of that. I am the total nut.

We’re just in training for the proper jail. Nobody talks about it, but it’s a statistical fact. That or on the game. Most of us are anyway – but not everybody. Some go to the nuthouse. Some just disappear.

The policeman unbuckles his seatbelt and checks there’s nothing worth choring on the dash.

‘Here we go.’ He opens his door.

One of the girls whistles, long and low.

‘Less of that,’ he glares up.

‘I wasnae whistling at you, pal,’ she says.

The baseball-cap lassie spits.

‘Dinnae give your mind a treat, we meant the hot one!’

They’re still giggling when he rams his hat on and clicks open my door. The policeman guides me up, hand on my head, turns me around – beeps the car alarm on.

The blonde girl lets her long globule of saliva fall away. The polis walk either side of me. I keep my shoulders back, my gaze even – almost serene. I dinnae walk with a swagger, just a certainty. As we reach the main door, I look up and it passes between us: the glint, it’s strong as sunlight and twice as bright. They can feel it in me. It can start a riot in seconds, that glint. It could easily kill a man.

I give the lassies my sweetest smile and lift an imaginary hat as a salute.

‘Ladies!’

The blonde girl grins at me. The policeman takes my elbow and steers me under the porch where they cannae see, and he rings the bell and I stamp my feet lightly, once, twice. I already know what it’ll smell like in there. Bleach. Cleaning products. Musty carpets. Cheap shite. Every unit smells the same.

There’s wire through the front windows but not the side ones. They’ll be easier tae smash. I try to breathe easy, but I want these fucking cuffs off, and my neck aches, and I’m starving. I want a milkshake and a vege-burger with cheese.

The policeman rings the bell again. My heart’s going. I’ve moved fifty-one fucking times now, but every time I walk through a new door I feel exactly the same – two years old and ready tae bite.

It’s open-plan inside. Nowhere to hide. That sucks. The Officer in Charge waddles towards us; she’s got a shiny bowl-cut, stripy socks, flat red shoes, and a ladybird brooch on her cardy.

‘Hello, hello, you must be Anais. Come in, officers, please come in. Did you get lost?’ she ushers us through the door.

‘Noh, we’re later than intended, sorry about that. We didnae want tae hold Anais’s transfer up, but it couldnae be helped,’ the policeman says.

He smiles and takes his hat off. He’s such a two-faced fuck.

‘We thought Anais was arriving yesterday,’ the Officer in Charge says.

She witters to the polis and I trail along behind them, turning around once, twice, looking at every single detail – it’s important to place where everything is. So nobody can walk up behind you.

This whole building is in a big curve, like the shape of a C, and along the curve on the top floor are six locked black doors. The two landings below have another six identical doors on each floor, but they’ve been painted white, and none of them are closed. I heard they dinnae close the doors in here except after lights out. It’s meant tae be good for us, ay. How is that good? Even from down here you can see bits of people’s posters in their rooms, and a kid sitting on a bed, and one putting on his socks.

Each of those bedrooms used to be a cell. Embedded in each door frame there are wee black circles where the bars were sawn off. I wonder why they kept nutters in cells? I suppose it was so each inmat

e could only see the watchtower, they couldnae see their neighbours. Divide and conquer.

Kids begin to step out of their rooms and look down. I count them out of the corner of my vision – one, two, three, four, five. A boy with curly hair and glasses begins to kick the Perspex balcony outside his door. I dinnae look up. There will be time for all the nice fucking hello-and-how-do-you-dos later.

Right in the middle of the C shape, as high as the top floor, is the watchtower. There is a surveillance window going all the way around the top and you cannae see through the glass, but whoever, or whatever, is in there can see out. From the watchtower it could see into every bedroom, every landing, every bathroom. Everywhere.

This place has experiment written all over it.

My social worker said they were gonnae make all the nuthouses and prisons like this, once. The thought of it pleased her, I could tell. Helen reckons she’s a liberal, but really – she’s just a cunt.

The ground floor is mostly open-plan; there’s a lounge to the right of the main door, and opposite that four tables make a dining space in the corner. Three doors lead off the main room, probably to the laundry, interview rooms, maybe a games room – if that’s a pool table I can see through there! There’s a telly screwed to the wall so nobody can chore it. The DVD player will be in the office, same reason.

They’ve painted everything magnolia and it all smells like shite deodorant, and stale fag smoke, and BO, and skanky, fucking-putrid soup.

At the end of the main room, opposite the door to the office, there is a wee ornate wooden door, one of the only original things left in here. I’ll investigate what’s through there later. This place would have been nicer once, more Gothic. It’s been social-work-ised, though, it’s depressing as fuck.

The polis come tae a halt outside the office door, and the Officer in Charge goes in. I scan the ground floor, and tap my feet, and clink my cuffs together until the policewoman leans over and says: Stop.

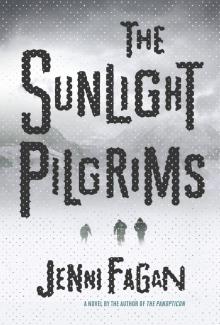

The Sunlight Pilgrims

The Sunlight Pilgrims